The Proton Mystery: AI’s Shocking Discovery

Hello friends, and recent discoveries have revealed that what we’ve been learning about the atomic model in schools and colleges is actually incorrect. Scientists, using Artificial Intelligence, have proven that the fundamental structure of protons in atoms is different from what we previously believed.

Proton’s Unexpected Composition

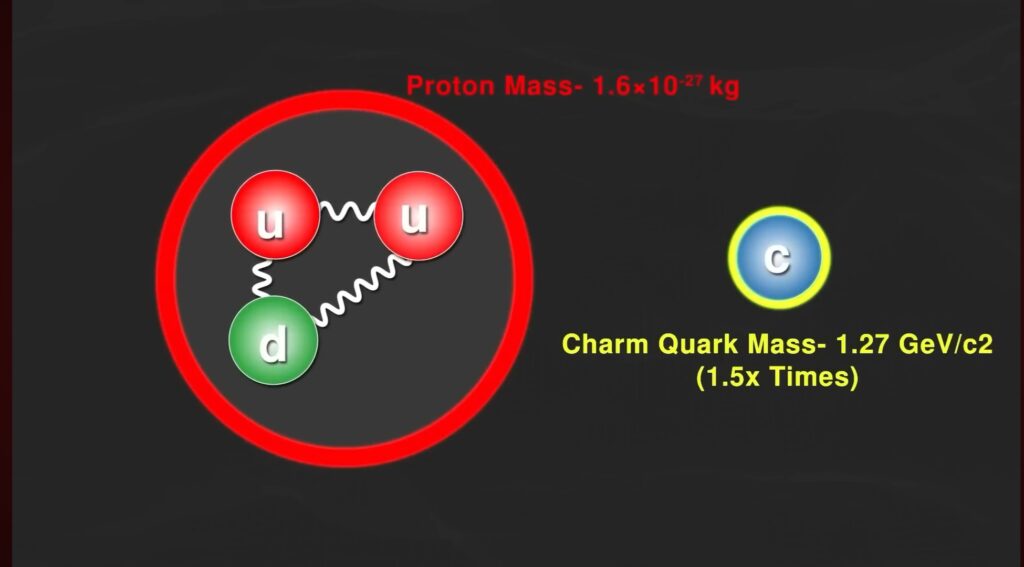

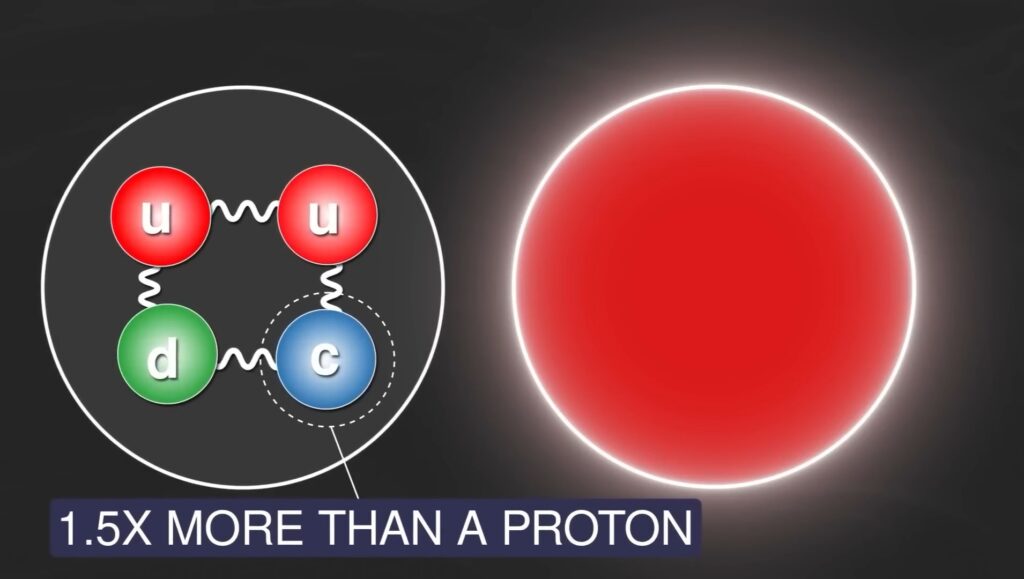

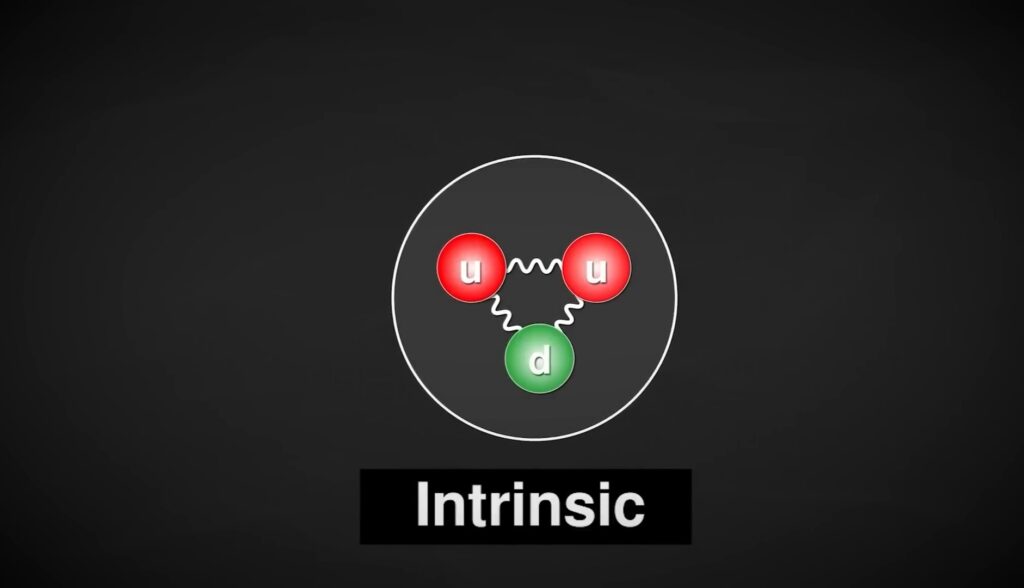

Protons are known to contain up and down quarks. However, new findings show that they also contain charm quarks. Surprisingly, a charm quark’s mass is 1.5 times greater than that of a proton itself, making its presence theoretically improbable. Yet, this has now been practically proven.

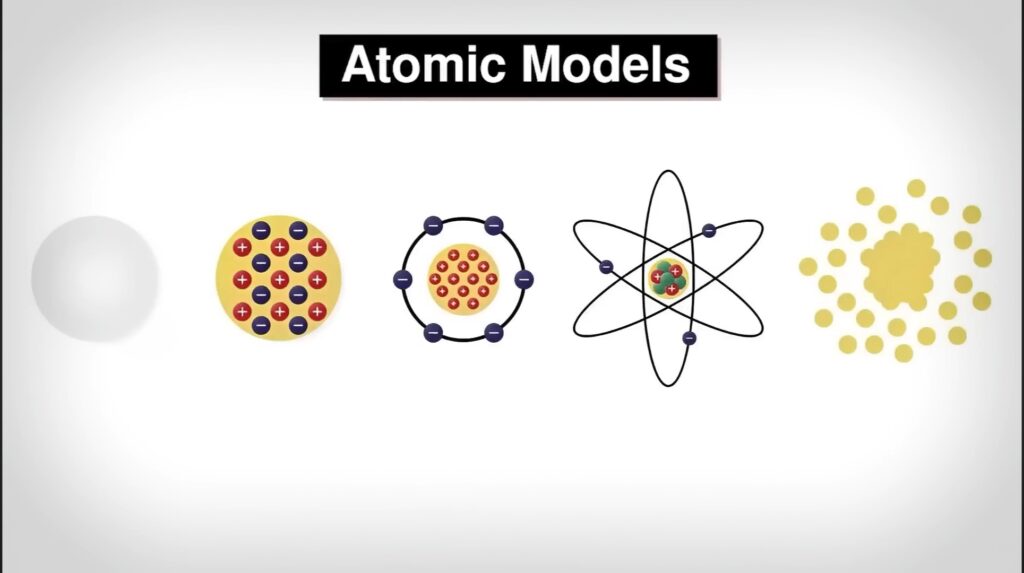

The Evolution of Atomic Models

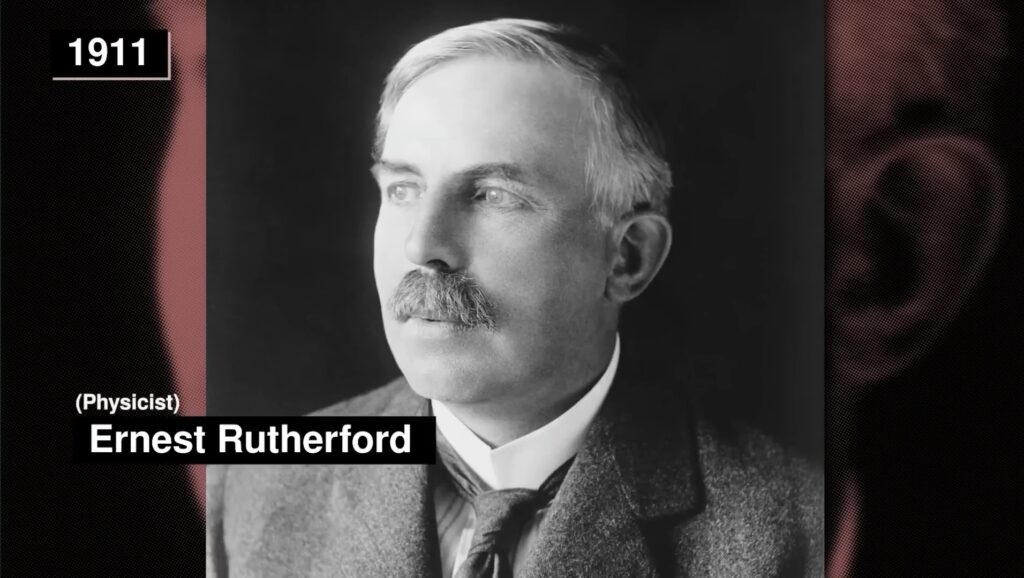

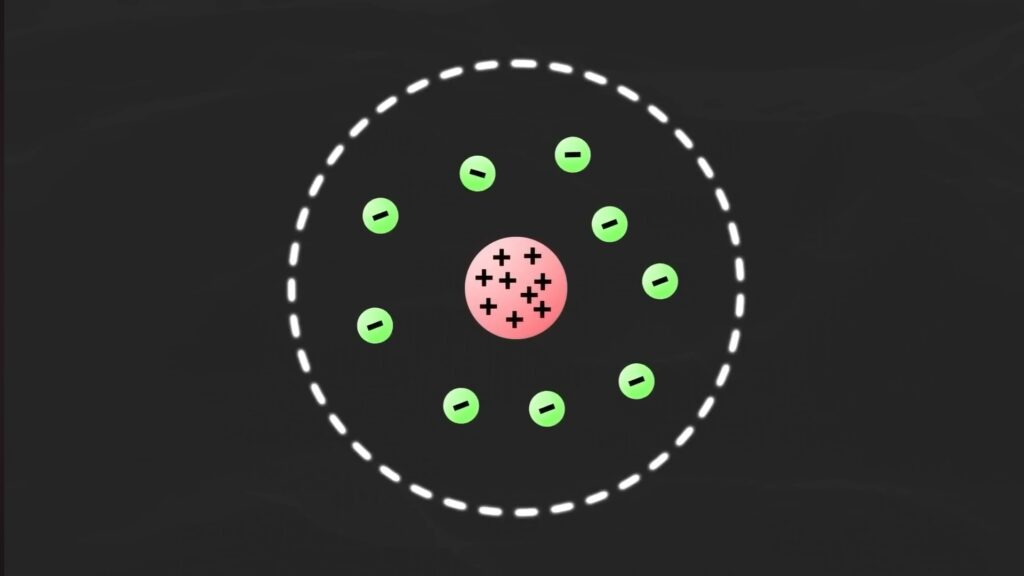

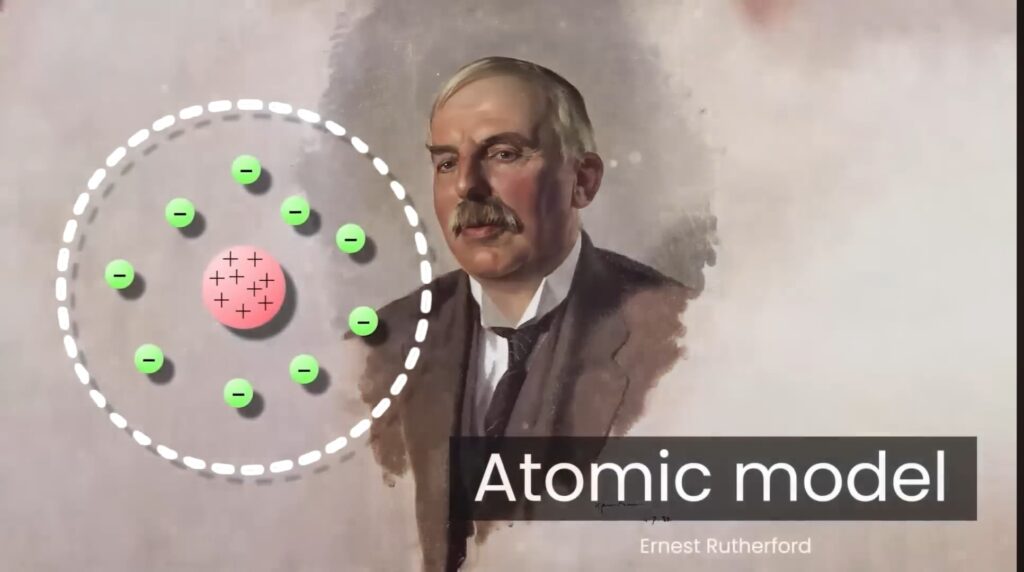

In 1900, atoms were believed to be the smallest particles. But in 1911, physicist Ernest Rutherford challenged this with his famous Gold Foil Experiment, where positively charged alpha particles were directed at a thin gold foil. Most particles passed through, but some bounced back, indicating a positively charged center — the nucleus.

Rutherford’s Atomic Model

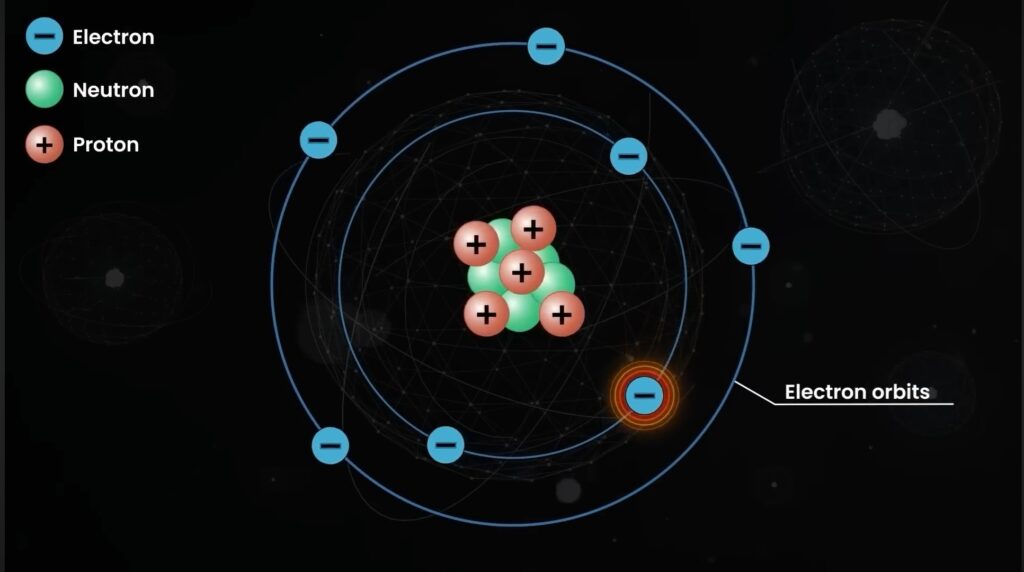

Based on this experiment, Rutherford proposed a model where protons and neutrons resided in the nucleus, while electrons revolved around it in circular orbits. However, this model faced a flaw — classical physics predicted that electrons would emit radiation, lose energy, and spiral into the nucleus, making the atom unstable.

Did Big Bang Never Actually Happen?

Did Big Bang Never Actually Happen?

Bohr’s Improved Atomic Model

In 1913, Rutherford’s student, Niels Bohr, revised the theory. He introduced the idea that electrons move in fixed orbits without radiating energy unless they jump between these orbits. This improved model became widely accepted due to its strong evidence and logical explanations.

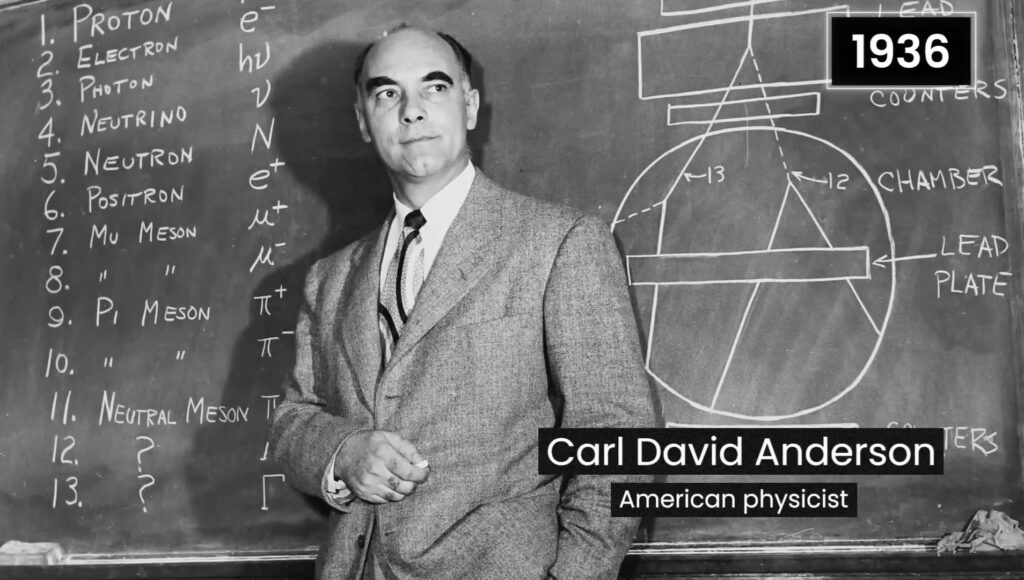

Discovery of the Muon

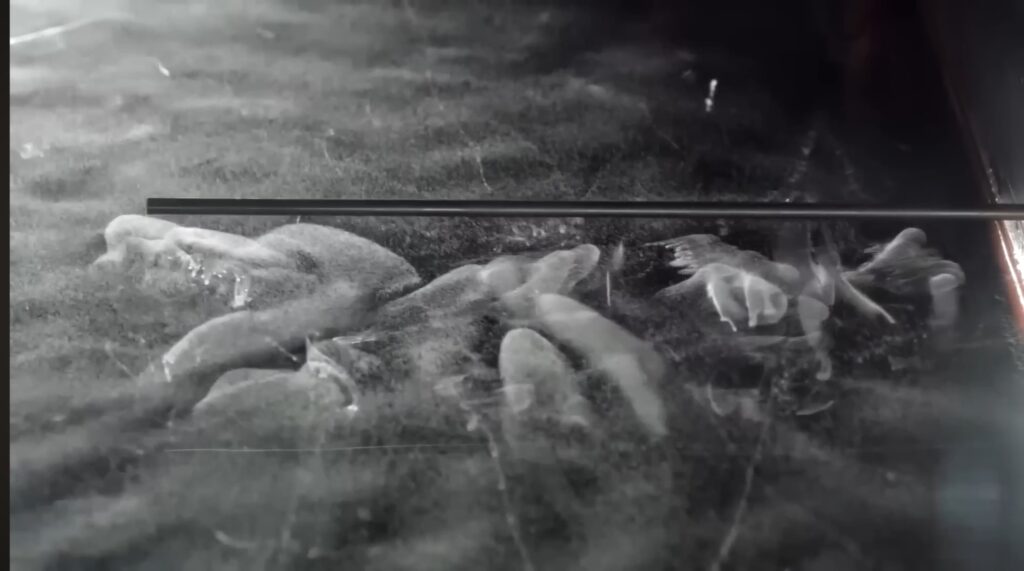

In 1936, American physicist Carl Anderson discovered a new particle called the muon. During an experiment using a cloud chamber — a device that nearly freezes water vapor — Anderson observed negatively charged particles similar to electrons but with greater mass.

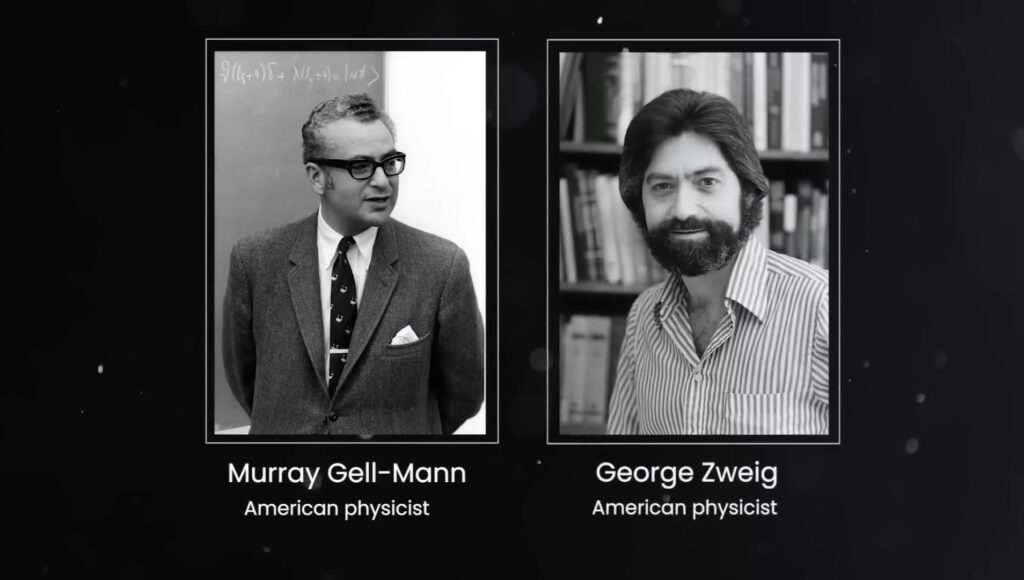

The Emergence of Quarks

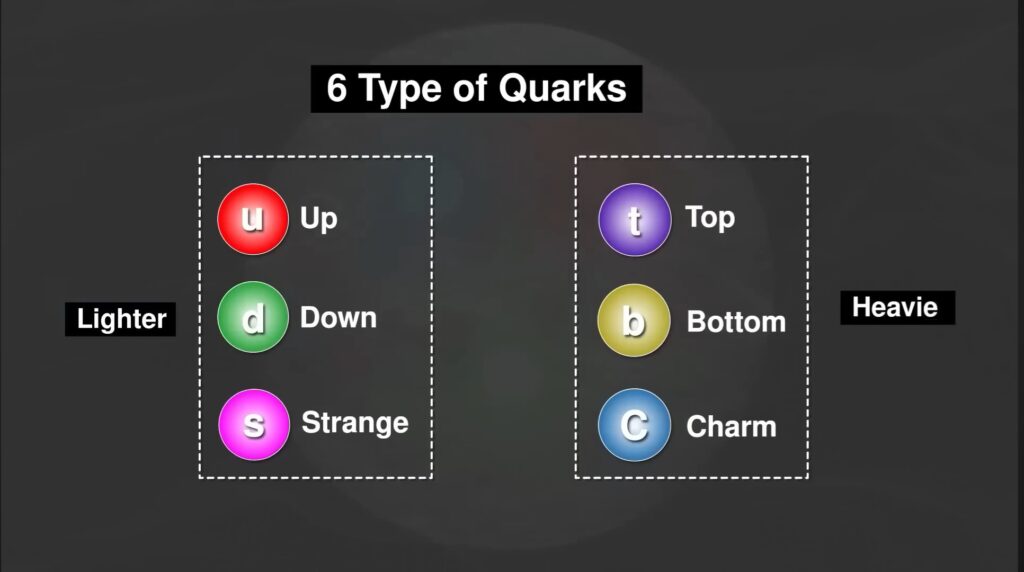

Over time, scientists discovered even more particles that didn’t match the known properties of protons or electrons. In 1964, physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig proposed that these particles — including protons — were made up of smaller fundamental particles called quarks.

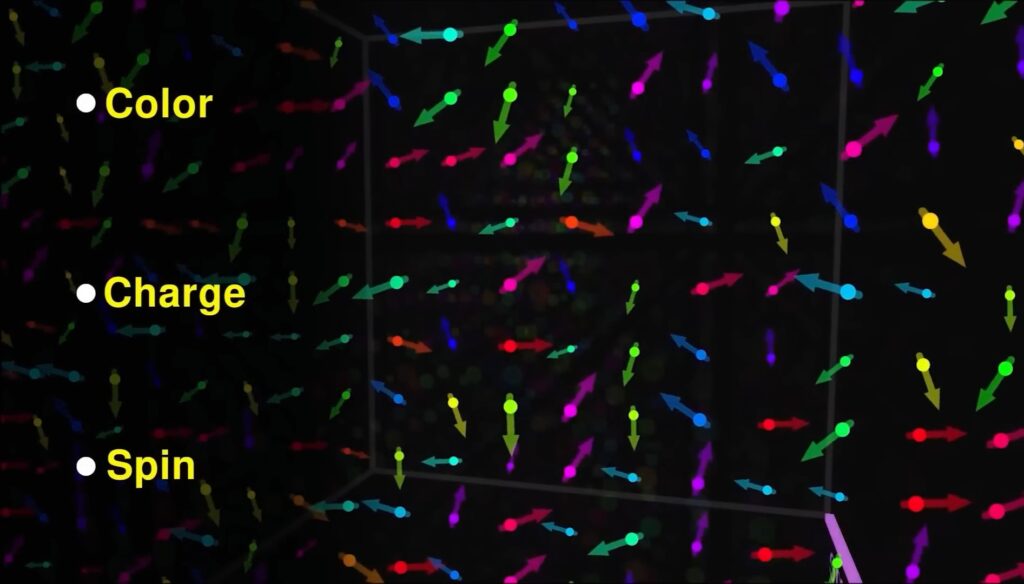

In 1964, a theory was presented suggesting that all particles, including protons, are made up of elementary particles called quarks, which determine the quantum properties of these particles, such as charge and spin. This theory was initially a hypothesis, so scientists began working to gather experimental proof.

Since these particles are incredibly small, scientists had to repeat experiments multiple times with electrons at different speeds to detect them. During one such experiment, they unexpectedly discovered a charm quark in the proton, which seemed impossible because the charm quark’s mass is 1.5 times greater than that of a proton.

Why North Pole star Polaris acting weird?

Why North Pole star Polaris acting weird?

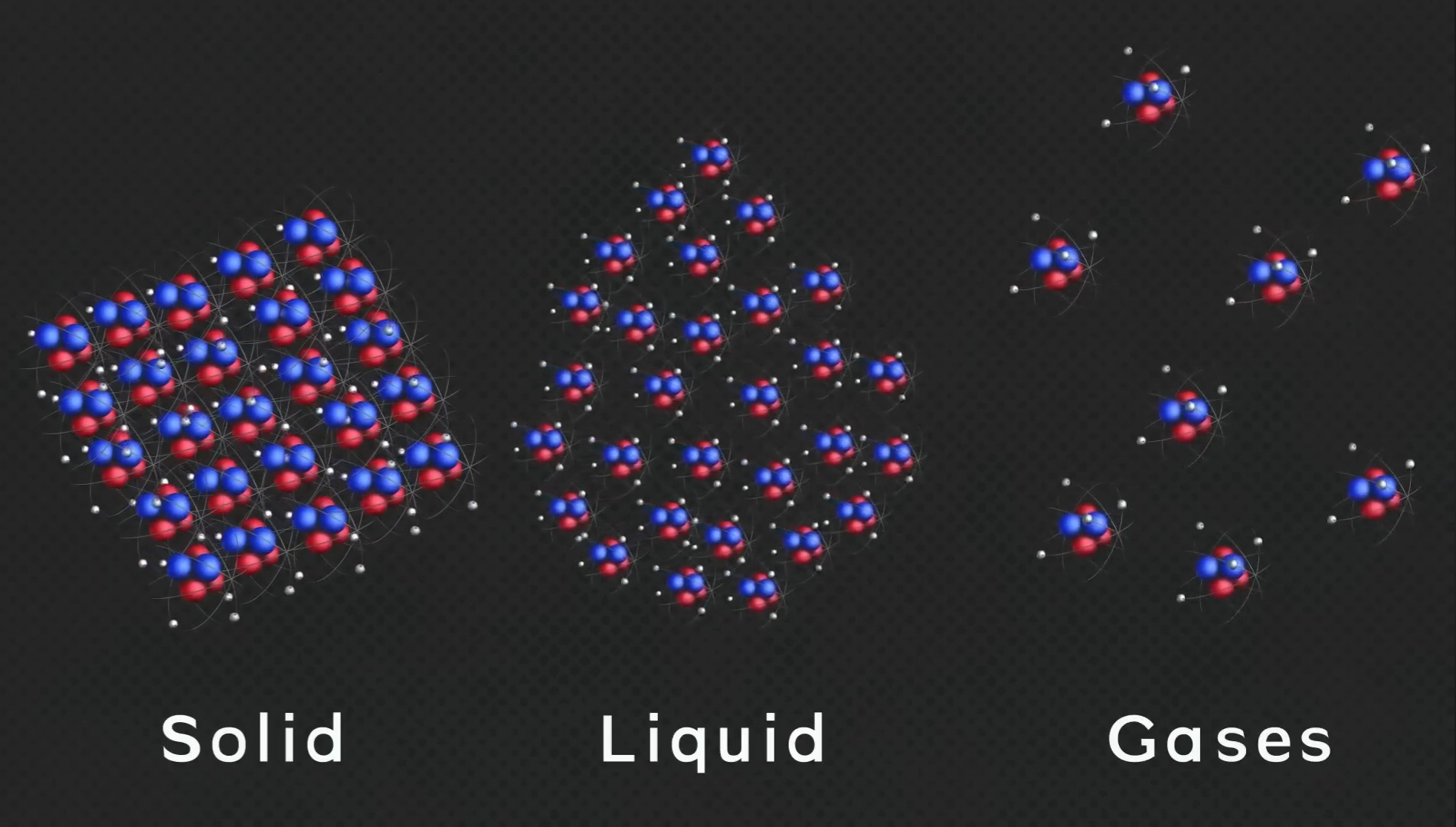

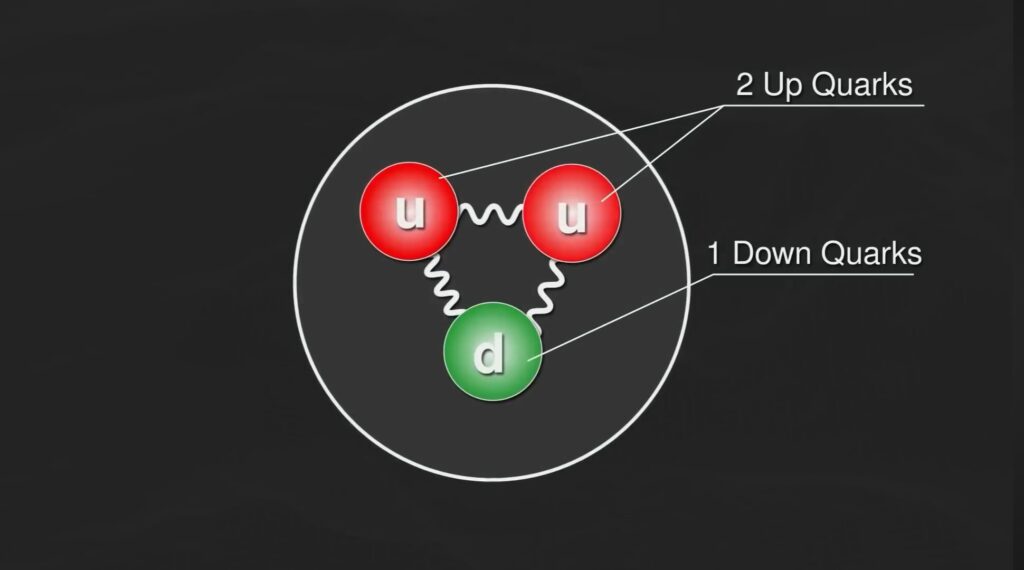

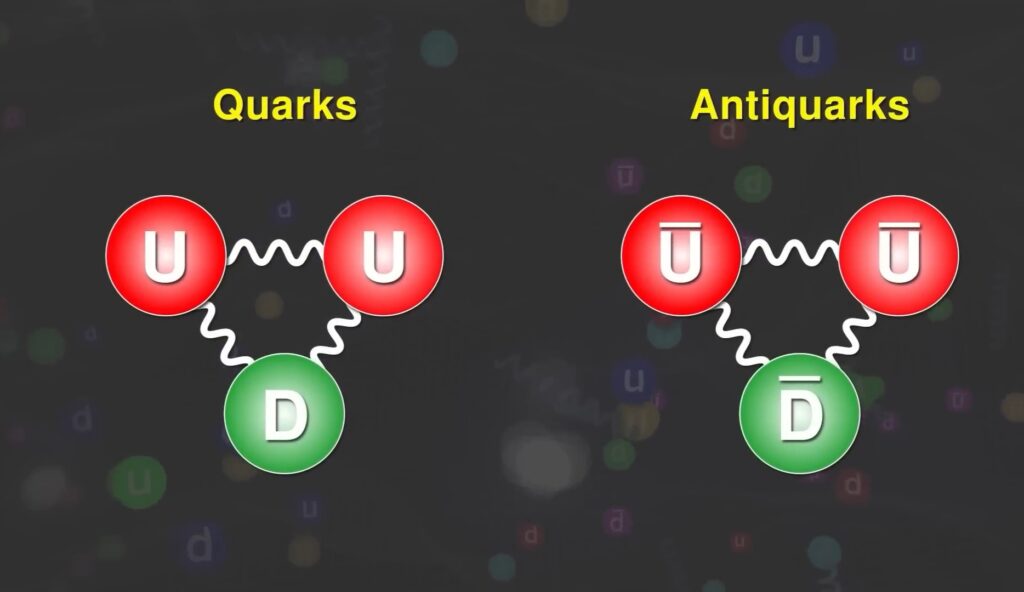

As a result, scientists initially believed that protons were composed of only two up quarks and one down quark. However, with the advancement of quantum physics, this model was challenged. According to quantum physics, protons have no fixed structure and are not made of just three quarks. Instead, they are a “quark sea,” where both quarks and antiquarks exist.

When a proton is captured, to conserve its quantum properties like color charge and spin, these quarks cancel out with their respective antiquarks, leaving only three quarks. This was the accepted understanding until scientists decided to study protons in greater detail.

As we now know, there are six types of quarks: up, down, top, bottom, strange, and charm. Among these, up, down, and strange are on the lighter side, while charm, bottom, and top are heavier. Since charm quarks are the lightest among the heavier quarks, scientists decided to first attempt to detect charm quarks within the proton model.

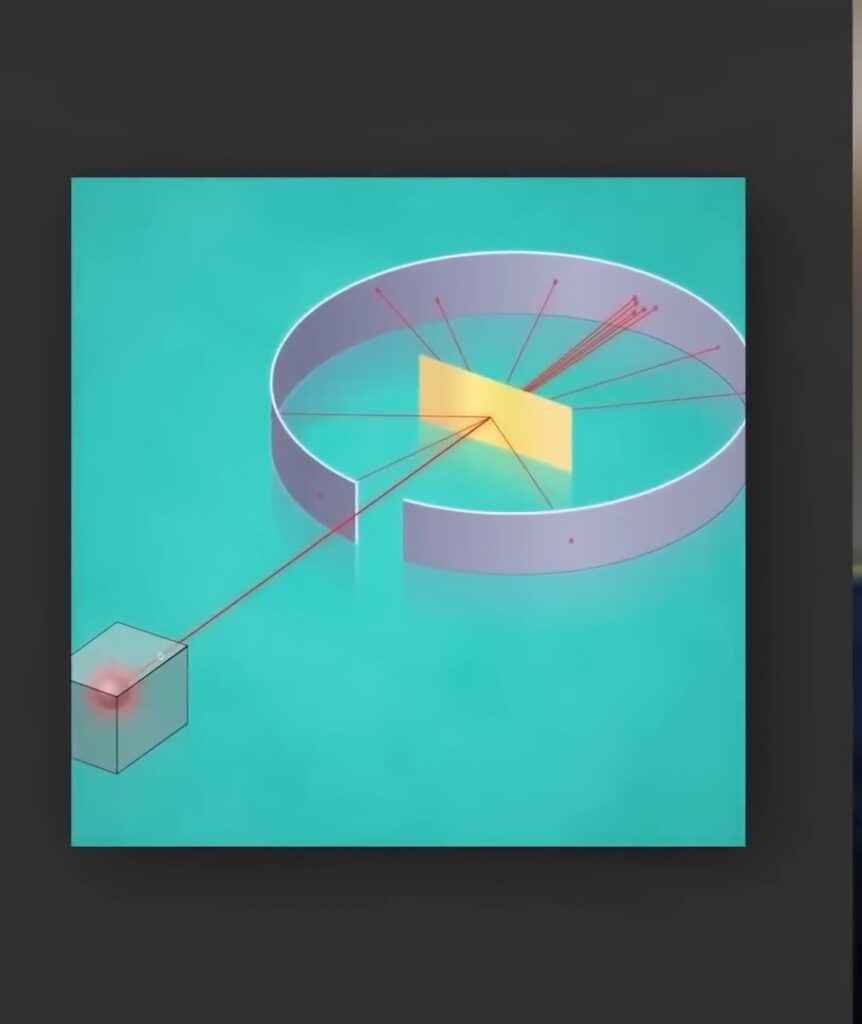

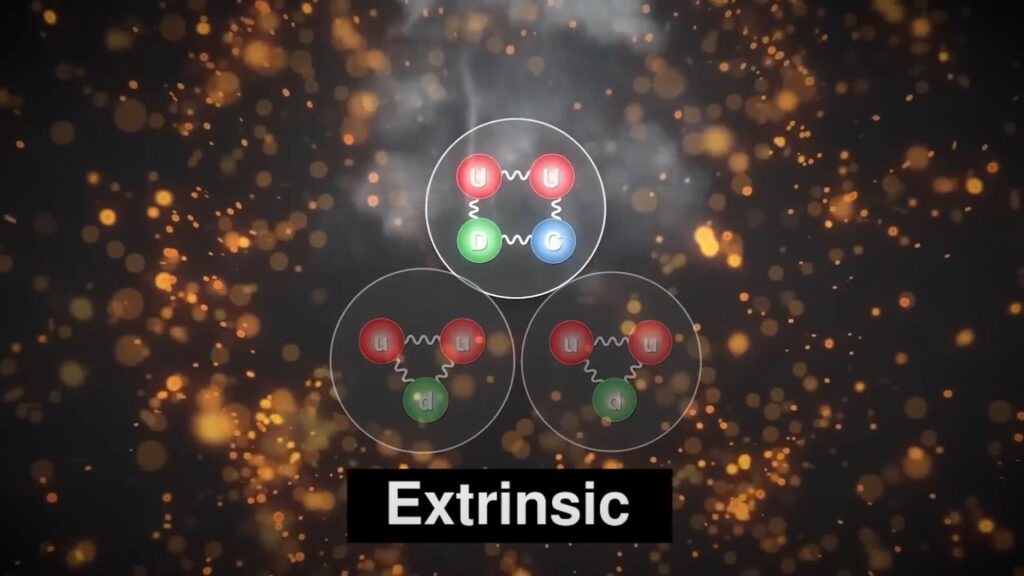

To explore the proton’s inner structure further, scientists used the world’s largest atom smasher — the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) — to collide protons at high speeds for several years. However, the results were quite surprising. While charm quarks were indeed detected in these collisions, there was no clear evidence indicating whether they were intrinsic (naturally present in protons) or extrinsic (created by external factors).

Some scientists suggested that these detected quarks were formed from gluons — particles that hold quarks together through the strong nuclear force. According to scientists, these quarks were likely a result of how gluons behave at high energies. This observation led scientists to speculate that charm quarks might exist even at lower energies, prompting further research.

Eventually, researchers realized that manually conducting this process would take several years to obtain accurate results. This led to the idea of utilizing artificial intelligence (AI). With AI, they could simultaneously test hundreds or even thousands of proton models rather than examining one model at a time.

For this AI-based testing, scientists trained a neural network using proton collision data collected over the past 35 years. Since every fundamental particle has its own wave function (its physical state), the scientists input the wave functions of up, down, and charm quarks into the AI and analyzed the proton collision data.

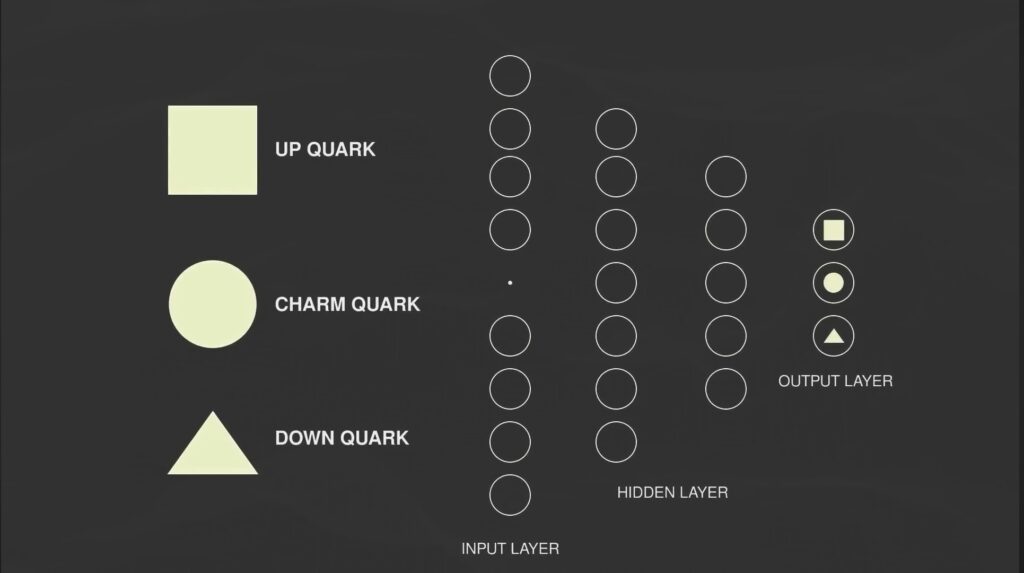

To explain how this neural network analysis worked, consider a simple example. Neural networks have three layers:

- Input Layer – Receives input data.

- Hidden Layer – Performs all computations.

- Output Layer – Predicts the output.

Imagine a circle representing the charm quark’s wave function, a triangle representing the down quark’s wave function, and a square representing the up quark’s wave function.

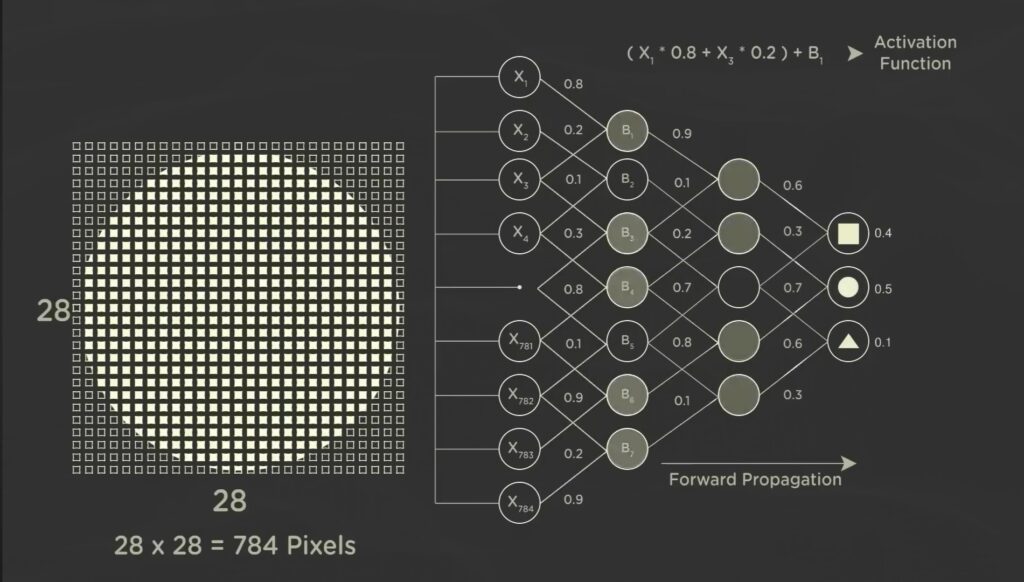

The process starts by dividing the circle (representing the charm quark) into pixels. Each pixel’s information is then passed on to neurons in the input layer. Neurons in the input layer are connected to neurons in the next layer (hidden layer) through channels, each having its own assigned weight.

These weights are multiplied with the information from the input layer, and the resulting output is transmitted to neurons in the hidden layer. Each neuron in the hidden layer has its own numerical value, which is added to the incoming values before being sent through an activation function.

The activation function determines which neurons in the hidden layer should activate. The activated data is then transmitted to the output layer, where the same process repeats. This entire process is known as forward propagation.

In the output layer, the neuron with the highest value activates and detects the final output.

And that’s all for today! See you in the next blog — until then, stay curious, keep learning, and keep growing.